The game Snakes and Ladders is a board game that originated in India a very long time ago. Americans probably know the variant Chutes and Ladders from Milton Bradley, which was first published in 1943. Anybody who has played it enough knows that it can sometimes take a large number of turns to complete, as you keep landing on snakes/chutes that take you backward on the board. This post attempts to quantify exactly how long it can take.

There are variations on the number of squares and placement of the snakes and ladders. For the first part of the discussion I will be using the configuration of the Chutes and Ladders game I own, altough I’ll use the term “snakes” instead of “chutes”, since I’ll be generalizing later to other configurations, and since I’ll be simulating the game using the Python programing language :).

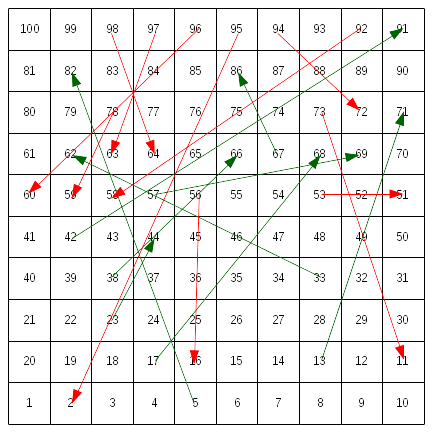

There are 100 spaces, 9 ladders, and 10 snakes. The following figure shows the board with ladders in green and snakes in red.

We can estimate the average number of turns by first considering a board with with no ladders and no snakes. The average spin or roll, having 6 possibilites, is 3.5. Therefore the average number of turns to reach the end would be . Next we consider the contribution of the snakes and ladders, by finding the total number of spaces the ladders move one forward, and the total number of spaces spaces the snakes move one backward. By subtracting the latter from the former we get

. We can approximate the impact of the snakes and ladders by assuming the configuration is similar to a board with no snakes and ladders that is longer than the current board by 33 spaces, which accounts for the fact that typically the combination of snakes and ladders move the player backward 33 spaces. Then the average number of turns to reach the end would be

. I don’t claim that this is an exact calculation or completely mathematically rigorous, but it should be a decent estimate.

To see how close this estimate is we can simulate the game in code. Then we can have the computer play many games and record the number of turns for a player to win. Then we can look at any statistical properties of the game data we want. The following is a Python program for simulating Snakes and Ladders and creating histograms of the game data using matplotlib and numpy.

# Snakes and Ladders simulation

"""

Copyright (c) 2016 Vernon Miller

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of

this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in

the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to

use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies

of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do

so, subject to the following conditions:

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all

copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER

LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM,

OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE

SOFTWARE.

"""

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from random import randint

board = {1:38, 4:14, 9:31, 16:6, 21:42, 28:84, 36:44, 48:26, 49:11, 51:67,

56:53, 62:19, 64:60, 71:91, 80:100, 87:24, 93:73, 95:75, 98:78}

def game(players):

"""Plays one game and return the number of turns taken to win"""

positions = [0 for i in range(players)]

turns = 0

while max(positions) < 100:

for player in range(players):

positions[player] += randint(1, 6) # position after spin/roll

if positions[player] in board:

positions[player] = board[positions[player]]

turns += 1

return turns

N = 1000000 # Number of games to play

nplayers = 1 # Number of players

nbins = 50 # Number of histogram bins

nturns = [] # List to store results

# Play

nturns = []

for i in range(N):

nturns.append(game(nplayers))

nturns = np.array(nturns)

print(np.min(nturns), np.max(nturns), np.mean(nturns))

fig = plt.figure()

plt.title("Players = %d" % nplayers)

plt.xlabel("Turns")

plt.ylabel("Probability")

plt.hist(nturns, bins=nbins, normed=True)

fig.savefig("plot1.png")

plt.hist(nturns, bins=nbins, normed=True, cumulative=True, color="blue")

fig.savefig("plot2.png")

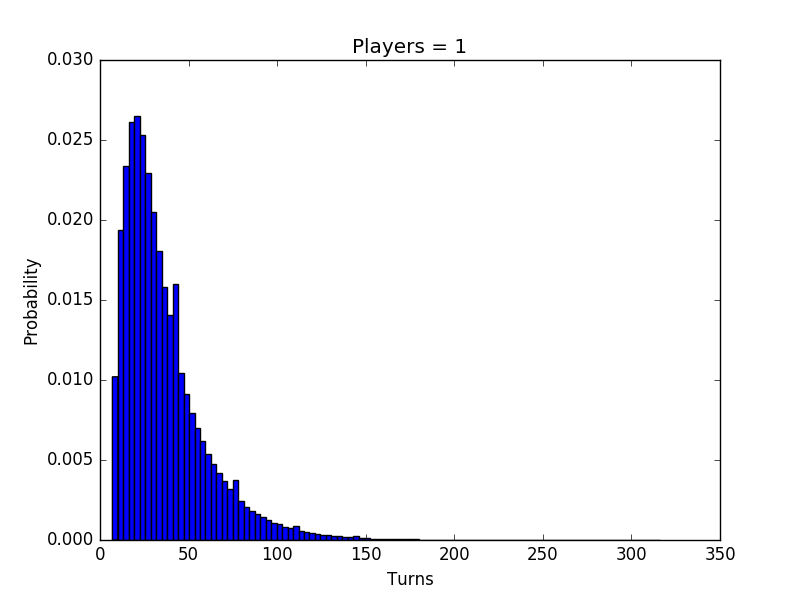

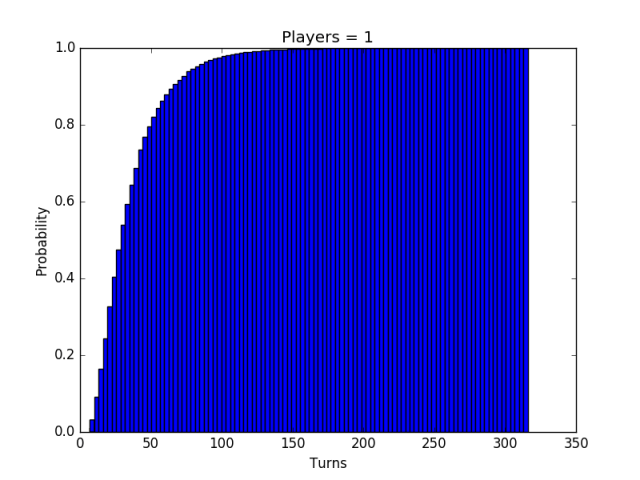

The program produces two histograms that correspond to the probabilty density function and the cumulative density function, respectively. If we play one million single player games we get the following two histograms.

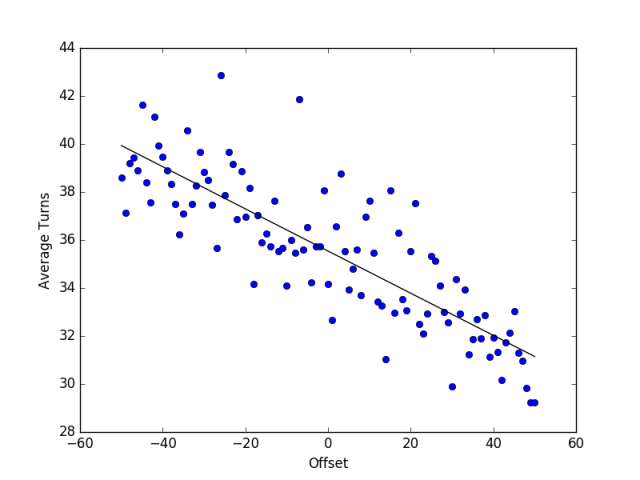

How typical is this particular outcome given the configuration of the board? Could we construct some non-trivial configurations that would result in significantly fewer or more average number of turns? Since it’s easy to simulate any configuration we might as well experiment.

First let’s contstrain the configuration to exactly 10 snakes and 9 ladders, just as we had before. Next, we can define an offset as the net spaces moved backwards or fowards by the combination of snakes and ladders. In the previous example this was -33. In python, if we represent the board as a dictionary as in the example above, then calculating the offset is a one liner:

board = {1:38, 4:14, 9:31, 16:6, 21:42, 28:84, 36:44, 48:26, 49:11, 51:67,

56:53, 62:19, 64:60, 71:91, 80:100, 87:24, 93:73, 95:75, 98:78}

offset = sum(map(lambda x:x[1]-x[0], board.items()))

The reason for defining the offset is that I’m curious is there is a simple dependence on the offset and the average number of turns. I assumed there was earlier when I tried to estimate the number of turns, but a simulation can check. Another constraint will be to limit the offset to be greater than -50 and less than 50.

The procedure then is

- Generate a random board with 10 snakes and 9 ladders.

- Only use boards whose absolute offset is less than 50.

- Simulate many games and record the min, max, and mean number of turns.

- Print to the stdout the board configuration for simulations that lead to >2X or <0.5x the average number of turns compared to the base configuration so they can be simulated further later on.

- Get a cup of coffee or tea while the simulation runs

- Plot the offset vs the average number of turns.

Below is the code for this procedure. It can run for quite a while depending on the number of board configuration to try. For 10,000 boards it ran for roughly 1 hour. I’m sure this could be improved by using the multiprocessing capability of python.

# Snakes and Ladders simulation - random sampling of board configurations

"""

Copyright (c) 2016 Vernon Miller

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of

this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in

the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to

use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies

of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do

so, subject to the following conditions:

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all

copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER

LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM,

OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE

SOFTWARE.

"""

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from random import randint

def get_board(snakes, ladders):

board = {}

choices = range(1,101)

for s in range(snakes):

a = choices.pop(randint(0, len(choices) - 1))

b = choices.pop(randint(0, len(choices) - 1))

if b > a:

board[b] = a

else:

board[a] = b

for l in range(ladders):

a = choices.pop(randint(0, len(choices) - 1))

b = choices.pop(randint(0, len(choices) - 1))

if b > a:

board[a] = b

else:

board[b] = a

return board

def game(board):

"""Plays one game and return the number of turns taken to win"""

position = 0

turns = 0

while position < 100: position += randint(1, 6) # position after spin/roll if position in board: position = board[position] turns += 1 if turns > 100000: # give up to account for impossible to win boards

return 0

return turns

N = 10000 # Number of games to play per iteration

I = 10000 # Number of iterations

# Play

simdata = {} # map offset -> [[min, max, mean], [min,max,mean],...]

for i in range(I):

acceptable_board = False

while acceptable_board is False:

b = get_board(10, 9)

offset = sum(map(lambda x:x[1]-x[0], b.items()))

if abs(offset) <= 50: acceptable_board = True nturns = [] for j in range(N): nturns.append(game(b)) nturns = np.array(nturns) mean = np.mean(nturns) if offset in simdata: simdata[offset].append([np.min(nturns), np.max(nturns), mean]) else: simdata[offset] = [[np.min(nturns), np.max(nturns), mean]] if mean > 100 or mean < 15:

print i, offset, np.min(nturns), np.max(nturns), mean, b

# Analyze and plot the data

x = []

y = []

points = []

for key, value in simdata.iteritems():

mins, maxs, means = zip(*value)

avg_mean = sum(means)/float(len(means))

points.append([key, avg_mean])

points.sort()

x, y = zip(*points)

# find a trendline

line = np.poly1d(np.polyfit(x, y, 1))

fig = plt.figure()

plt.xlabel("Offset")

plt.ylabel("Average Turns")

plt.plot(x, y, "o")

plt.plot(x, line(x), color="black")

print line

plt.show()

There are some differences between this and the first program, besides the fact that it generates random board configurations according to a range of offsets. The simulation is restricted to a single player, and there is now a maximum number of attempted turns on a given game before giving up. This is because for random placement of snakes and ladders there are some configurations that are unwinnable and would therefore run forever in a simulation. For example if squares 94 through 99 are each the start of a slide, and there is no ladder that ends directly on 100, then the game is unwinnable. I chose a maximum number of turns of 100,000, based on running many simulations and never seeing anything close to that as a valid maximum.

One question that comes to mind is how many different board configurations are there with 10 snakes and 9 ladders? I assert that the answer is the same as the number of combinations of selecting 38 items from 100 choices, or

To prove that this is the correct number I can show that any sequence of 38 randomly selected squares from the board can be used to construct exactly 10 snakes and 9 ladders. Let the list of randomly selected squares be written as . Now let them be broken up into 19 pairs

. Next sort each pair, resulting in a new list

, where

and

. Finally we will define two operators. A right arrow

when placed between squares

represents a ladder connecting two squares. A left arrow

when placed between squares

represents a snake connecting two squares. Place a

between the squares of the first 10 pairs, and place a

between the squares of the last 9 pairs. There are then 10 snakes and 9 ladders. Since the inital list of squares was arbitrary the value for the number of combinations holds.

I don’t have enough time to evaluate all 5.6 octillion configurations, so I’ll have to settle for random sampling. The chart below shows the average number of turns (for 10,000 games) for 10,000 random board configurations with varying offsets from -50 to 50.

Or, with the help of WolframAlpha, we can make the coefficient more memorable and gratuitously complex.

Where is the average number of turns and

is the offset.

Let’s take a look at the equation and ask if it makes sense. At first glance by putting in zero for the offset we get 35.54 for the average, and that may seem at odds with the earlier estimate of 28.6 for a board with no snakes and no ladders. However it does make sense because having a zero offset is not the same as having no snakes and ladders, because in all these simulations there were 10 snakes and only 9 ladders. That means that you are more likely to land on a snake than a ladder, and therefore more likely to increase the number of turns to complete the game, even with an offset equal to zero.

If we plug in the offset of -33 from the original configuration into the equation we get 38.5 as the average number of turns. This is pretty close to our initial estimate of 38. There are two things to keep in mind however. We only sampled 10,000 board configurations out of the possible octillion+ possibilities, so with more sampling the fitted line could become more accurate. Also, there are significant outliers, especially those having an average much higher than what would be predicted.

An example of one of the outliers is the board shown below.

An outlier on the low side is shown below.

Summary

- Snakes and ladders has a long tailed distribution for the number of turns required to complete a game, as anybody who has played more than 4 or 5 games has probably experienced.

- Calculating an offset based on the particular snakes and ladders provides a decent way finding an average number of turns to complete a game, according to the equation

, but there are outliers that deviate significantly.

- Python, matplotlib, and numpy are great tools that make simulating games like this very straightforward.

Copyright (c) 2016 Vernon Miller. All Rights Reserved.